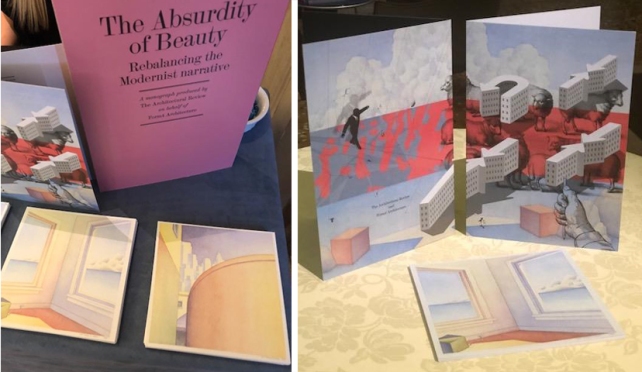

In this series, we are publishing excerpts from Form4 Architecture’s monograph: The Absurdity of Beauty – rebalancing the Modernist narrative. Our third post focusses on an essay written by the British architectural critic, Jay Merrick, who spent his formative years growing up in California. We are delighted that Merrick used his early impressions of living on the West Coast to reflect on what makes Californian architecture distinct as it plays on a unique mythology that has put the state on the world map from the days of the Gold Rush and well into the 20th and 21st centuries.

The inclusion of a chapter on Californian architecture in this monograph examining the Modernist narrative was important to us not least because we are a San Francisco based practice. The story of California and its own brand of culture has therefore shaped the way we design. Californian landscape, light and climate and the early adoption of environmentalism have all played their part; as has its free spirited entrepreneurial outlook that has been the backbone of Californian society from the early pioneers to today’s tech giants. The success of Silicon Valley has also coincided with the Bay Area’s approach to workplace interiors becoming globally influential. These interiors support a collaborative and flexible approach to work that is very much of California. This made us want to reflect on the roots of the innovations that Californian high tech companies have introduced to not only office design per se, but to office life around the world.

The title of Jay Merrick’s essay “Designing at Evolving Frontiers” hints at the way he sees the journey Californians have taken as changing with the times, whilst creating a thriving contemporary culture that is often ahead of its time. How this journey is expressed in the local architecture is something Merrick captures with great flair and insight.

“Designing at Evolving Frontiers” by Jay Merrick – Extract:

“The museum’s curator, Justin McGuirk, links Californian existence with Jean Baudrillard’s definition of an achieved utopia – a place that ‘allowed itself to imagine it could create an ideal world from nothing’.

Facebook’s start-up motto in 2004 was ‘Move Fast And Break Things’, an ethos of fearless invention which had already been demonstrated in architecture such as Greene and Greene’s 1908 Gamble House – the so-called ‘ultimate bungalow’ – and Irving Gill’s remarkable, proto-minimalist 1916 Dodge House in West Hollywood. In the 1930s and ’40s (and leaving aside California’s early Modernist houses), aesthetic-formal frontiers had been breached by vividly outré, neon-edged Popluxe (aka Googie) architecture, such as Wayne McAllister’s faux-futurist Simon’s Drive-Ins, and the boomerang-canopied Harvey’s Broiler outlets.

In 1960, John Lautner’s pedestalled octagonal Chemosphere was the apotheosis of space-age domestic Modernism and, 18 years later, the weirdly discombobulated Gehry Residence in Santa Monica was an instantly legendary lift-off moment for Deconstructivist design.

Simultaneously, the countercultural ideas and output of artists, writers, and environmentalists became key influences on Californian architecture. Ed Ruscha’s laconic photographs in Twentysix Gasoline Stations, for example, were produced five years before the publication of Learning From Las Vegas. ‘I’m interested in glorifying something that we in the world would say doesn’t deserve being glorified’, said Ruscha. ‘Something that’s forgotten, focused on as though it were some sort of sacred object.’

Equally sacred in Californian architecture are compelling fusions of Modernism and environmentalism – contradictory, tense, potentially fertile. Charles Moore’s blocky cascade of clifftop condominiums at Sea Ranch, 100 miles north of San Francisco, was brilliantly novel in 1966. The noted architectural critic Paul Goldberger said it was, ‘the ancestor of virtually every California beach house and Vermont ski house with unpainted wood siding, a boxy form and a slanted shed roof – one of the few buildings of our time that has become part of the vernacular’.”

Read more about theabsurdityofbeauty.com

The above drawings relating to this blog post 11/4/18 are all by Pierluigi Serraino, AIA.

Pierluigi is a San Francisco Bay Area based architect, author, and educator. His work and writings have been published in professional and scholarly journals. He has authored and contributed to several books, among them Modernism Rediscovered (Taschen, 2000), Eero Saarinen (Taschen, 2005), and The Creative Architect: Inside the Great Personality Study (Monacelli Press, 2016). His latest book is California Captured (Phaidon, 2018) on architectural photographer Marvin Rand. His forthcoming book is a comprehensive appraisal of architectural photographer Ezra Stoller (Phaidon, 2019).

Regarding his interest in hand drawing historic buildings, Pierluigi notes, “Drawing is a way of knowing. What is learned in the process of re-drawing the icons of modernity and previous eras? A world of content unfolds and a higher awareness of the scope of architecture as an art form.”

In our series of extracts from The Absurdity of Beauty – Rebalancing the Modernist narrative we wanted to include an excerpt from writer Sam Lubell and his essay “Rethinking Silicon Valley”. Sam edited the California edition of The Architects’ Newspaper over many years and is currently a staff writer at Wired magazine. His interests and knowledge of the Bay Area thus made him uniquely placed to write about Silicon Valley in The Absurdity of Beauty. His essay on the architecture of the Silicon Valley is an insightful description of the urbanistic challenges office developments for high-tech industries continue to face as they are built ever further afield.

In our series of extracts from The Absurdity of Beauty – Rebalancing the Modernist narrative we wanted to include an excerpt from writer Sam Lubell and his essay “Rethinking Silicon Valley”. Sam edited the California edition of The Architects’ Newspaper over many years and is currently a staff writer at Wired magazine. His interests and knowledge of the Bay Area thus made him uniquely placed to write about Silicon Valley in The Absurdity of Beauty. His essay on the architecture of the Silicon Valley is an insightful description of the urbanistic challenges office developments for high-tech industries continue to face as they are built ever further afield.

This week we are celebrating two cultural projects we have worked on over the last year with Architectural Review (AR) Magazine and the Global Art Affairs (GAA) Foundation in Venice. Both projects, one a publication and the other an exhibition, although different, have risen out of a sense of advocacy at Form4 Architecture.

This week we are celebrating two cultural projects we have worked on over the last year with Architectural Review (AR) Magazine and the Global Art Affairs (GAA) Foundation in Venice. Both projects, one a publication and the other an exhibition, although different, have risen out of a sense of advocacy at Form4 Architecture. Next week sees the opening of our exhibition at Palazzo Mora in Venice organized by the Global Art Affairs (GAA) Foundation. The overall theme of the exhibits hosted by GAA is “Space – Time – Existence”.

Next week sees the opening of our exhibition at Palazzo Mora in Venice organized by the Global Art Affairs (GAA) Foundation. The overall theme of the exhibits hosted by GAA is “Space – Time – Existence”.